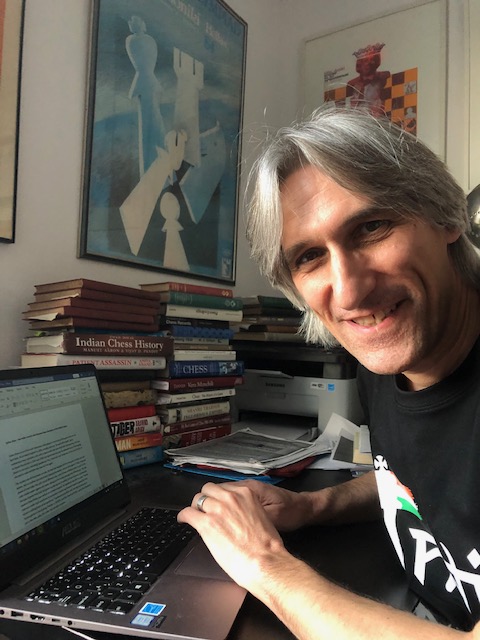

(Captured by Lennart Ootes)

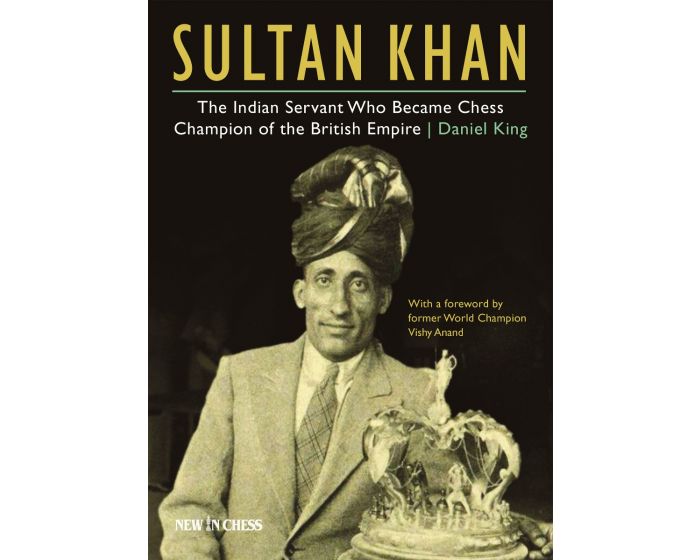

Grandmaster Daniel King is an incredibly famous figure in chess circles. A commentator, presenter, author, and coach – he dons a number of hats and excels with each of them. Recently, he wrote the book titled ‘Sultan Khan: The Indian Servant Who Became Chess Champion of the British Empire’. He also released a Powerplay DVD on the King’s Gambit only a week ago. There couldn’t have been a better time to reach out to Daniel for an interview, and he promptly agreed despite his thoroughly hectic work schedule. In the following interview, he talks to Shubham Kumthekar about his book on the legendary Mir Sultan Khan, shares stories surrounding the great man, and discusses his contribution to the game of chess. Daniel further explores his own love for the King’s Gambit and reviews the romantic opening’s current state. Finally, he talks about what it is like to be Daniel King to wrap up a highly detailed interview!

Shubham Kumthekar: How did the idea of this book come together?

Daniel King: I always knew about Sultan Khan as I have played a bit in the British Championships, and I know something about the British Championships! Somehow, he was this mysterious figure and I didn’t know his story very well. But then a theatre director, who was interested in his story, approached me. He asked me to do some research on his behalf and I began researching. The more I looked into it, the more interesting the story became. With many stops and starts, I ended up gathering all this research, all this material. For me, it was just a hobby. I was just collecting little bits of information. I would be going up to the British Library and looking up the newspapers from the 1920s and 1930s. At some point, I realized I had collected all this information and I thought to myself – should I leave this or should I organize the material and do something with it? That’s when I decided okay, let me organize the material and turn it into a book!

But the thing is, I have a very full working life. As a result, it took me years to write this. Sometimes I wouldn’t touch the material for like 6 months and then I would have a week where I could devote myself to it. Then again, I would be traveling somewhere, commentating somewhere, and it would get difficult to find the time. Eventually, I got there in the end. The more I looked into it, the more intriguing it became. The political story behind it became more interesting. Also, I discovered more about Sultan Khan as a person – he comes across as a very sympathetic person, and I didn’t want to spend my time with a person I didn’t like! I feel like I got to know him over these years!

What are the other forays into chess history that you make as part of this book?

The chess scene at that time in Europe and in England was fascinating. Of course, you had all these great figures like Alekhine and Capablanca (at the global level). But even on the English Chess scene, you had all these incredible characters who were talented in their own right… Like Yates, Thomas, Winter, Alexander. It was very interesting looking at their lives as well and how Sultan Khan interacted with them. I was just intrigued by the whole project, and I would like to continue researching, to be honest. I enjoyed it so much!

I got a lot of information (about the Indian chess scenario) from this book called the Indian Chess History written by Manuel Aaron and Vijay Pandit. I got a lot of biographical details of the Indian players from that book, but also from other books and newspapers. And again, these were remarkable characters. VK Khadilkar, of course, was the first Indian to play in the British Championship in 1924. So he was a trailblazer for Sultan Khan, which I found very interesting. Khadilkar didn’t do badly – he scored a little under 50%. He lost his first 4 games and I am guessing that maybe he had trouble with the food, maybe the climate, maybe the travel. But after those first 4 games, he rallied and actually played some very nice games as I show in the book. He was sponsored by some of the Indian princes to come to Britain – his expenses were paid by some of the Maharajas. I found it incredible. In some ways, it’s similar to the story of Sultan Khan, who wouldn’t have come to England if it wasn’t for Colonel Nawab Sir Umar Hayat Khan. All in all, I was intrigued by the whole story.

Writing this kind of book is hardly a piece of cake. It has its own set of challenges. You have to be politically and historically correct in every sense of the business that you are going about. What kind of challenges did you face?

Exactly the ones you have mentioned. Of course, historical accuracy is of utmost importance. As such, I was extremely careful to quote my sources. However, I am also acutely aware of the history of our countries. I wanted to put something that I felt was right and proper. If you see in the book, I detail the kind of opinions that were prevalent at the time in London, in the United Kingdom, and also in India, and try to balance them. It’s actually quite a nuanced picture because in the United Kingdom, you had a large section of the population who accepted the Empire. For them, the Empire was normal and India was part of the Empire. They didn’t see a problem. On the other hand, there was also a very large section of the society that was against the Empire. So for instance, when Mahatma Gandhi came over for the India Roundtable Conference in 1931, which I talk about in the book, he was enormously popular with a large section of the population here. At that time in the 1930s, there was a very strong peace movement in the country. And naturally, he was very popular with them and with lots of church people as well. He went off to the north of England where there were strikers for example, in the cotton mills. He was extremely popular even there and was surrounded by crowds of people. Even for my father, Gandhi was always a hero. This is true for many intellectuals. Such stories aren’t very well known. But of course, there was another huge part of the population, which thought he was a troublemaker. And they didn’t understand the independence movement at all. And I talk about this kind of things in the book, because I want to put the historical background in perspective.

Sultan Khan wasn’t political. However, his patron – or we can say his master – Sir Umar was. He was an advisor to the British government and fought with the British Army. There was also a section of the Indian population that was loyal to the British. This is also a part of the story. Overall, it’s a very nuanced picture, and I am very aware that it’s quite possible to put a foot very badly wrong here. However, including the historical background is also important because that is why Sir Umar came to London. He was on his political mission.

I was very very careful with checking dates – dates for games and other activities like simultaneous displays and official events that Sir Umar went to. I checked very carefully with different newspapers to make sure I got them right. A lot of the dates I found on ChessBase for the games weren’t correct. So it was like a jigsaw puzzle – I had to put it all together.

Was there an attempt to reach Sultan Khan’s family?

I didn’t. Of course, I really hope they like the book because I want to pay tribute to Sultan Khan as a great player. One of the reasons that I didn’t reach out to his family was that I had done all this research and somehow, I didn’t want the word to get out about it. I wanted to make sure that the book sort of arrived intact. Also, most of my research was done about his time in Europe. As such, all the sources that I required, I could look them up here (in UK).

Of course, there are more details to be found about his early life in Punjab and his life after going back to India, and I would be very interested to learn more. I could have kept researching forever. And in the end, I realized I needed a cut-off point because it was taking over my life.

Yeah, it’s already a reasonably thick book at 372 pages…

Yeah, and I already cut it down! I’m serious. I thought that I had to draw a line somewhere.

I agree. When you talk about a book, it’s imperative we talk about its target audience. Are we looking at this book as a historical account, or can it also be used by people for the betterment of their chess?

I actually think that both those things are true. I mean, if you want to study some of Sultan Khan’s games, I think they’re very valuable. He was brilliant at the endgame. He played some fine strategic middlegames. His openings may have been erratic and poor, some of them really poor. But sometimes, he discovered things that were really pretty good and groundbreaking! For example, he played 4.a3 in his famous game against Capablanca. This later became popular as the Petrosian variation against the Queen’s Indian! I find this really interesting, this is one of his opening experiments that was very successful. It went on to become a main-line of the Queen’s Indian. You had arguably one of the greatest players in the history of the game – Garry Kasparov – playing a3. That is when you realize that Sultan Khan understood something about the game. In the 1920s, only a handful of players played 4.a3. But I don’t think Sultan Khan would have been copying them. He wasn’t a researcher like this. And so when he played it, I am sure that he was basically improvising. I find it pretty fascinating that sometimes, he really did hit upon something that was pretty good.

Hastings 3031, 1930.??.??

So, of course, we can learn from him. Another thing that we can learn from him is his tenacity. He could turn games around. He was extremely hard working at the board. And it shows that focus and concentration during the game are so important. Sometimes you have to check-in and just bury yourself. Some players can do it better than others and Sultan Khan was brilliant at it.

Sultan Khan was not as well studied at chess as his contemporaries. He was a natural player. Did this actually make him more modern in some sense than his contemporaries?

That’s really interesting! Because in a sense, he was being a pioneer, he was improvising a lot of his openings, he made some interesting discoveries. There’s one particular game where his play is quite incredible. He plays a kind of hedgehog setup with Black. It came from a Nimzo Indian and he ended up playing f5, g5-g4, h5-h4-h3. He had this pawn chain d7, e6, f5, g4, h3 in a middle game when he was attacking the White King on g1. This is really hypermodern. I cannot imagine any English players (of those times) playing in this fashion! It was a wild game and the advantage swung back and forth. But Khan won in the end. However it’s the style of it – I just thought, wow, this is really something special. So I think you have made an interesting point. I have never put it like that myself that in some way he was kind of ahead of his time. I think I may have done something a little bit like that. But I didn’t say that he was kind of a modern player. He was a different player. And he was experimenting. And I suppose that’s the way that chess strategy develops.

He actually had a 2-0 record against Capablanca, didn’t he….

Well, you can’t really count a simultaneous game! But the story of that simul is quite extraordinary. I find it incredible that he played in this simul. I think the people didn’t know how strong he was. Also, I think he didn’t know how strong he was! He had just arrived. He hadn’t really faced any Western opposition. He had been in the country for only two days. No one knew anything about him!

Because of his background and the kind of player he was – not very strong in the openings, very natural, not so known in Europe. Do you think he was underestimated by some people on the scene? And did that play a role at times?

I don’t think they underestimated him. I think they appreciated his strength. And of course, he did develop as a player. I think we shouldn’t forget that. His openings did get much better. Even at the end of his career, he had disasters. But on the whole, his openings got much, much better. In some of the games that I show in the book, he was playing quite an orthodox strategy on the black side of the Spanish – really good. Also, he always played the Queen’s Gambit Declined with black and won some really nice games. That was always part of his repertoire. His repertoire definitely expanded – with white he definitely developed. When he first came to London, he was playing 1.e4 a lot and he was really shaky. He didn’t play well against the Sicilian. He looked like he had never really encountered the Sicilian before. But after about a year and a half, he switched to playing 1.d4, and he was much, much better with 1.d4 That was a really positive move to switch mainly to 1.d4. He still played 1.e4 occasionally, but with d4, he was much more solid. I think it suited his style far better. But even there, he experimented. Often he would play 1.d4 and then he wouldn’t play 2.c4, and instead played Nf3, g3, and Bg2. He loved the fianchetto.

And the stonewall sometimes…

Yes, and the Stonewall! Again, it’s a system. He liked systems – not variations but systems.

So he used to play this system with fianchetto and he would allow his opponent to play c5 and then he would just play c3. It’s like a reverse Grunfeld. And he managed okay, mixed as ever. He liked to play with black. Hence, he may have thought: I might as well play this way with white!

Coming back to your point about Sultan Khan being quite a modern player… there’s a certain player who I saw play this exact system – Carlsen himself against Caruana! If you have a look at that game, Carlsen basically did exactly what Sultan Khan used to do. Carlsen played 1.d4, then fianchettoed on g2, c3 and when Fabi played c5, Carlsen took on c5.

Vugar Gashimov Mem 2014, 2014.04.30

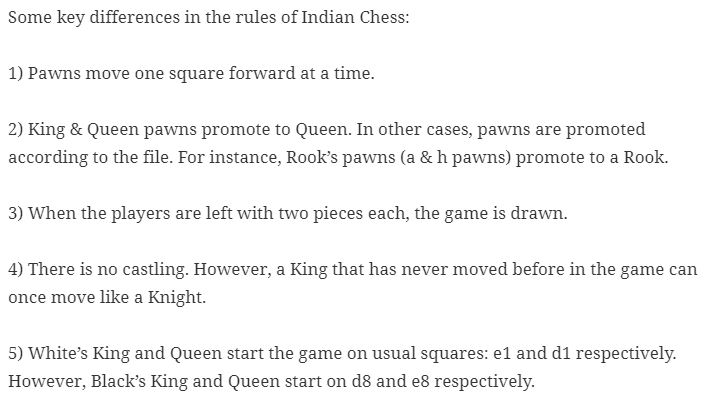

In relation to Sultan Khan, you also talk about the old Indian variant of Chess in your book. Do you think the old Indian Chess, like Chess960, could be a possible alternative to normal Chess?

That’s very true! Maybe not the rules at the end of the game, but you could start with pawns having just one step like the old middle-eastern game. This is like Kramnik’s variant – no Castling. In fact, Kramnik’s variant in some ways is closer to the original Indian game.

The other new thing that you recently released is the Powerplay 27 – King’s Gambit DVD for Chessbase. How and when did you first get acquainted with the King’s Gambit?

There is this book called the Game of Chess. This is the first chess book that I ever read – it belonged to my father. I still have it. It is a little bit tatty and there is a sticking tape on it. I’m afraid to open it as it may fall apart!

In that book, Golombek shows you how the pieces move. He also gives some historical games. And the first game there is the Immortal Game – Anderssen vs Kieseritzky. When you see such a game, it makes a big impression on you. You think this is a great opening! So as a teenager, I used to play the King’s Gambit. I loved it and it was good fun. When I got to about 18 it was perhaps time to grow up a little! I played the Spanish which I have always loved. But the King’s Gambit – for many years I played it and had great fun with it. It is kind of in my blood. As such, it was interesting to go back and look at all these old lines and see what is good and what works well. I reviewed a lot of these variations for the first time in decades. And I found it incredibly interesting. There are things like the Fischer’s Variation (1.e4 e5, 2.f4 exf4, 3.Nf3 d6) which, he claimed was the bust of the King’s Gambit in his famous article in 1963. However, it is probably one of the variations which gives white the most chances! Acknowledged King’s Gambit experts like Nigel Short and Joe Gallagher say that this is one of the variations where they feel the most confident with White. And rightly so. It gives White very interesting chances. You may check out the game Short against Akopian – beautiful game! But even in variations which are supposed to be fine for black, the problem for Black is that the opening is so complex and it is incredibly easy to go wrong. That’s why players like Adhiban can get away with it. He still plays it now and again. You have Ponomariov playing it. You can check out the game Ponomariov against Dominguez – blows him away!

Madrid Magistral 6th, 1997.05.26

IMSA Blitz 2016, 2016.02.29

What kind of modern philosophy do you advocate for the King’s Gambit? Because the King’s Gambit in the days of Anderssen and the King’s Gambit today are completely different things, aren’t they?

I thought it was interesting to look at the opening with kind of modern eyes instead of my eyes when I was a teenager – back then they were romantic eyes! I think it’s about the initiative. If you are a bean counter, then it is probably not the opening for you. But if you want to create chaos and a complex position and show your imagination and have a lot of fun, then the King’s Gambit is your opening!

Also, people say, “Oh, the computer shows this line as better for black!” But once you get there, when you come to the board, you don’t play as a computer. You play as a human. And there is so much jeopardy in this opening that it is extremely difficult for Black to play. There are so many opportunities for White to create real chaos.

Very true. Black is quite often out of his territory, going away from the usual e4-e5 tabiyas...

I think it’s a really good point. I think one thing that you should take care of is which opponents you play the King’s Gambit against. Quite a lot of 1.e4 e5 players have a certain expectation of how the game will go. And they are obviously comfortable with playing these kinds of strategic games with a slightly symmetrical pawn structure. Then suddenly, they’re faced with the King’s Gambit, and this is not what they anticipated they would be doing for the afternoon! Looking at it they go, oh my goodness! It is also the kind of opening wherein your choices on the first few moves are critical. If you’re someone who is used to playing the Berlin with black, you are used to playing the first 20 moves in an endgame where you can make a slight inaccuracy and it doesn’t matter. In the King’s Gambit, if you make a slight inaccuracy, you can get checkmated! And this is a very different kind of story. It’s quite difficult for some players to adjust to this kind of chess.

Coming to something more personal. I am not the kind of person who watches chess videos much. But the only ones I truly enjoy are the ones on your channel. I am hardly kidding! What is it that you do in your videos or presentations that makes you different to other people?

You would have to ask others about that! Honestly, I have no idea. I just present as I do, and I suppose I have a lot of experience presenting on TV. Not just videos but you know working for the BBC, working for ESPN, stations in Germany, in the Middle East. I even found myself on Doordarshan! (Ed. – India’s national TV channel) Therefore, I just have a lot of experience staring into a camera and being able to present. Maybe this makes a difference. But honestly, if you ask me what am I doing differently, I have no idea because that’s just what I do. This is me staring into a camera!

Also, I am a journalist. I am used to wearing lots of different hats. I’m a coach. I’m an author. I’m a broadcaster, and I’m a journalist too. As such, I am used to writing a story. So when I do a video, I present a story. It is part of being a journalist.

The amount of work that you do is insane. I can simply sense it by looking at the number of videos on your YouTube channel and not even taking into account your videos for Chessbase and other work. What drives you, how do you keep going?

I am interested in the game, really interested! Yes, sometimes it’s nice to have a break – I like to spend time with my family. But it’s okay. I enjoy working. I think it’s as simple as that. I believe working gives you a purpose in life. Also, the variety is interesting.

One final question: How do you think is the chess scene going to change after this pandemic?

In many ways, the world of chess has pretty much gone in this (online) direction. I think the pandemic is kind of accelerating this trend, which has been taking place for years. I am not going to say ‘business as usual’. But yes, it’s accelerating the trend.

Can you replicate these big tournaments when people play remotely? That’s difficult, but Magnus seems to be achieving that at the moment. I think the problem comes when you’re trying to hold larger tournaments with prize money. The temptation to cheat… You can have controls, you can have people using webcams. But I think if someone is determined to cheat, frankly, it’s difficult to stop. But I notice, at the moment, there’s the Sunway Sitges tournament in progress. That’s a classical tournament’s online with hundreds of players. And I think that’s a fantastic initiative. Now, I don’t know the details. I don’t think there’s prize money. But they have organized it extremely well from the looks of it. Maybe the trend will be to play tournaments for honor – that would be nice. That way, it becomes a pastime and not a profession. There are lots of possibilities to make a living online with the prevalent situation through journalism and broadcasting.

So yes, it will be more difficult to hold tournaments with a lot of prize money. But maybe more of the top tournaments will go online because I don’t think the top players are going to cheat. I don’t think that’s going to happen. They have too much at stake. But at lower levels, I think it is a danger. Even in real over-the-board tournaments, there are still sadly cases of cheating. If you go online, of course people are going to cheat. I don’t think you can prevent it. And that’s why, I think, to play without prize money is not a bad thing. In the end, we are in it because we like playing chess!

– – – – – – –

Important links:

New in Chess link to the Sultan Khan book: https://www.newinchess.com/sultan-khan-hardcover-ebook

Amazon link to the Sultan Khan book: https://www.amazon.com/Sultan-Khan-Servant-Champion-British/dp/9056918745

Amazon India link to the Sultan Khan book: https://www.amazon.in/Sultan-Khan-Servant-Champion-British/dp/9056918745

Chessbase link to Powerplay 27 – King’s Gambit: https://shop.chessbase.com/en/products/king_powerplay_27_kings_gambit

Chessbase India link to Powerplay 27 – King’s Gambit: https://chessbase.in/online-shop#!/Power-Play-27-The-Kings-Gambit-By-Daniel-King/p/190773725